I recently heard a superintendent recount that she had been asked what she is looking forward to as students and staff return this fall. Sadly, she admitted that she struggled to give an authentic, positive answer. The pressures, stresses, and struggles of the past year combined with uncertainties regarding the lingering presence of the pandemic have robbed her of the excitement and anticipation that usually accompany the start of a new school year.

The admission was particularly striking to me because the superintendent is a skilled, committed, impactful leader. We can ill afford to enter the year already feeling defeated. It is particularly difficult to engage, inspire, and lead those who depend on us if we are not confident about and motivated and inspired by what lies ahead.

Rather than give in and allow what lies ahead to defeat us, now is the time to take stock and focus on how we can make this coming year the most impactful and successful of our careers. History is filled with examples of great leaders and leadership that prevailed in the face of what seemed like insurmountable challenges. Consider Winston Churchill’s circumstances as a leader in the early days of World War ll. England was standing alone in the face of Germany’s aggression. Its major cities were under daily attack, and many of Churchill’s advisors lacked confidence in his leadership and doubted his decisions. Yet, he knew that the strength of the nation was in its people and their resilience. His challenge was to engage their resilience and inspire their hope. In the end, the bombings they endured were a source of strength and pride, and a major force in their eventual success.

As we consider the start of a new year, we do well to identify the opportunities to lead and make a positive difference through our leadership. Those around us are depending on us and need our best thinking, judgement, and ideas. Here are some places to start as we position ourselves to lead and become inspired in this difficult, but potential-filled time.

We can remind ourselves and those we lead of what we accomplished, how we persevered, and why it matters now. We have learned much in the past year about ourselves, our work, our learners, and what can help us to succeed. We can give people permission to let go of regrets and less than successful efforts in favor of gleaning what was learned, celebrating successes, and taking pride in our resilience and persistence. We do not know what lies ahead, but we can be confident that we are better positioned and prepared than we were when we first faced the pandemic. We are more skilled, better informed, and a more potent force as we face the future.

We can continue to prove that educators matter. We need to celebrate the crucial role we play. The past year brought more attention to and appreciation for what it means to teach, guide, support, and protect learners and learning than any time in recent memory. Ironically, the current controversies about teaching are evidence that what we do matters. These times also call on us to be courageous on behalf of our students and their learning experiences. Now is the time when we can make the greatest difference in our work and for our profession.

We can make this a year for healing. We can look forward to rebuilding a culture of caring, belonging, and mutual support. Many of our students have experienced trauma and chaos in their lives and need understanding, acceptance, and tolerance as they recover. The same is true for our colleagues. Our opportunity in the coming year is to be there for people who need us. To support each other as we provide support to our students. This work can be truly inspiring and difference-making.

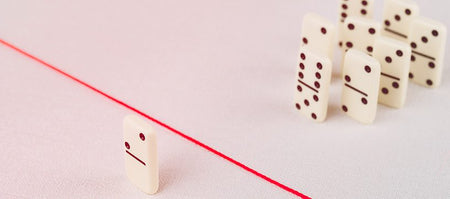

We can be a source of hope and optimism. Importantly, being optimistic is a choice. We can choose to focus on what is difficult and discouraging, or we can focus on building a path to a better future. We can claim hope and not allow the frustrations of the moment to distract us from long-term goals and eventual success. Hope and optimism are not “soft ideas” to be dispelled when challenged. Rather, they can be life sustaining and success-building tools that inspire despite our current reality. The people in our organization will depend on us as a source of hope and optimism to draw energy and inspiration from.

Interestingly, each of these items will have the effect of making our lives and work better, even worth looking forward to, as we make life, work, and learning better for others. Of course, we need to take care of ourselves, too, but making a difference in the lives of others is a great way to make our own lives better.

Tap Five Success-Generating Leadership Affirmations

Affirmations have long been known to be effective ways to shift thinking and pursue important goals in our personal lives. They have been shown to create clarity and focus our thinking. Affirmations can also help us to align our energy and attention in ways that produce tangible results.

However, we don’t often think about affirmations as contributing to leadership success. Yet, the same factors that can make affirmations useful tools to achieve personal goals can help us focus our professional attention, align our energy, and see opportunities that we otherwise might miss.

Regardless of life context, our thoughts are powerful shapers of how we see reality. What we tell ourselves influences our perceptions. What we think drives where we invest our energy and how we respond to experiences.

Affirmations help us to form intentions and shape goals. Of course, affirmations work when they are repeated, reflected upon, and regularly applied in our actions. The more frequently we say, think about, and act on affirmations, the more powerful their impact can be.

When affirmations become part of our leadership thinking and actions, they can help us to gain new insights, discover new strategies, and form stronger, more influential relationships. Let’s explore five leadership affirmations worth tapping in our daily thinking, actions, and routines:

- Keep the main thing the main thing. This affirmation can help us to remain focused when we face myriad issues and challenges and are at risk of becoming distracted by detail or overwhelmed by demands. Remaining focused on what matters most, whether student learning, health and safety, or instructional effectiveness, can help us to ignore what does not deserve our attention and energy and prioritize what does. This affirmation can prompt us to ask, “What really matters here?”

- The most important step in any journey is the next step. When beginning major projects or undertaking a challenging change process, we can become so focused on potential problems, strategies to employ, or what will be required that we forget that every journey is a series of steps and actions. We may want to immediately be at the end point. Or we may become overwhelmed with what lies ahead. Yet, what we do next will often play a key role in determining whether the ultimate outcome will be reached. The truth is that each step matters and the opportunity to make progress lies in taking the next step. We need to ask ourselves, “What is the next step that will move me forward?”

- Intentions matter more than motivation. At first, this affirmation might seem counterintuitive. Motivation creates energy and excitement for what may lie ahead. Yet, while motivation can be useful in getting started, it can lack focus and wane as the reality of the work and struggle necessary for success becomes evident. Intentions, on the other hand, position us to commit. Intentions can help us to focus our energy and carry us through when our motivation may not be as strong as it was at the beginning. We can “power through” even when our motivation wanes by asking, “What am I committed to and why does it matter?”

- Time is my most important resource. Each day we face requests, distractions, opportunities, and expectations that compete for our time. We may be inclined to respond as much and as often as we can, believing that engaging with people and responding to their needs and interests are important. While to an extent, this perspective makes sense, it overlooks an important fact. We have a limited number of hours and minutes each day. How we choose to use the time we have will determine our success and the extent to which we can serve the needs of those who depend on our leadership. We do well to ask ourselves often, “What is the best use of my time in this moment?”

- Gratefulness makes everyone’s day. Life is often hectic, even chaotic at times. We face multiple demands and must respond to varied situations. It can be easy to fall into a habit of finding fault, lamenting problems, and regretting actions taken, or not. Yet, during even the most difficult times, there are opportunities, experiences, and relationships for which we can be grateful. Reflecting on, appreciating, and sharing what we can be grateful for can immediately change our attitude, help us to reframe a situation, or lift the spirits of those around us. When gratefulness becomes part of each day, it makes each day better. We can summon these feelings by asking ourselves, “What can I be grateful for right now and who needs to hear it?”

Five Leadership Lessons From the Pandemic

Times of disruption, conflict, and crisis always shine a spotlight on leadership. The pandemic has not been an exception. Employees, students and families, and communities looked to those in positions of leadership in schools and school districts for guidance, judgment, clarity, and understanding.

The pandemic reinforced and, at times, amplified the importance of leadership skills and behaviors that we have always valued and expected from leaders. Leaders are expected to take steps to protect everyone. People look to leaders to consult with experts, make sense of what’s happening, and develop plans for the organization to follow.

As the pandemic unfolded, leaders were expected to maintain a focus on the mission and role of schools to educate students and support instruction despite the challenges and distractions. Leaders were looked to for acquisition and distribution of resources needed to allow instruction and learning to continue as effectively as practical.

Yet, within these larger leadership roles and expectations, the pandemic experience offered several specific lessons worth noting and heeding before the next extended, disruptive challenge emerges. Here are five of those leadership lessons and the implications associated with them.

First, relationships are key. We know the importance of relationships in the context of teaching and learning. The pandemic demonstrated that relationships are equally important for adults. Where leaders had developed strong, trusting relationships prior to the pandemic, stakeholders found it easier to accept leadership decisions and direction despite the fear and confusion they experienced. The pandemic taught us that we need to develop relationships before we ask people to trust us, do difficult things, and face the unknown. It was possible to develop trust and credibility during the pandemic experience, but too often it meant the loss of crucial time and sacrificed some early opportunities to respond. We also learned that when there is no relationship and trust is absent, asking people to take risks, engage without full understanding, and press forward despite uncertainty is likely to be futile.

Second, authenticity matters. People want to know that leaders really care and are not just “going through the motions” or “checking boxes” when they inquire about what followers are experiencing, questions they have, and answers they need. Perfunctory responses and generalized expressions of caring can leave stakeholders feeling dismissed and diminished rather than supported. Careful listening, empathetic responses, and honest commitment to follow-up are especially important when people are hurting, frightened, and uncertain of where to turn.

Third, positivity has its limits. While it is important for leaders to project a positive attitude and be optimistic about what is happening, messages they send must be grounded. Positivity must be connected to reality. When leaders ignore the level of pressure and stress people are feeling and project unfettered positivity, they risk perceptions of being disconnected and out of touch with what people are experiencing. Too much positivity without grounding can be toxic.

Fourth, strength does not mean having all the answers. Leaders often believe that to lead they must be fully in control and free of questions and doubt. Yet, the pandemic was plagued with uncertainty, unanswered questions, and changing conditions. In times such as these, leaders are often asked to lead without all the information they would like or need. Being willing to commit when commitment is called for, choosing to risk when action is necessary, and pressing forward when inaction would sacrifice the mission are steps leaders are called to take in times of crisis. Of course, even making the correct call does not always mean universal support and agreement.

Fifth, conflict is not always what it seems. Arguments over face masks, insistence on remote or in-person learning, and other pandemic-related issues were not always about safety and learning. The presenting conflict can be a proxy for other issues. Political perspective can override science. Childcare needs can prevail over risks of exposure to the virus. What people oppose or support can have as much to do with what they fear, personal priorities, and partisan politics as the importance of the stated issue with which they identify.

Without question, the pandemic reinforced what we know about the importance of leadership. It also invited us to learn the importance of less visible and more nuanced aspects of leading successfully during extended disruption.

Five Ways to Counter Uncertainty, Confusion, and Self-Doubt

There is no doubt that these are challenging times in education whether we are a teacher, administrator, or other staff member. In fact, these may be some of the most difficult times we have faced in our careers. We found our way through what appears to have been the worst of the pandemic, only to face lingering questions about the best way forward for students too young to be eligible for vaccination and young people who have yet to be or are choosing not to be vaccinated. At the same time, we face questions and challenges about the role and content of discussions about race and equity in our schools and classrooms. Of course, the challenge we face to help students whose learning lagged throughout the past year is far from met.

Disappointingly, the perspectives and concerns of others are too often accompanied by negative assumptions and accusations about our character and motivation rather than engagement in a search for consensus about the best course of action.

This level of conflict and pressure can leave us feeling uncertain, confused, and even in self-doubt. The nature of issues seems to shift week to week and month to month. Further, the underlying drivers of conflict are not always clear and knowable. And there are no easy or simple choices for the decisions we must make if we are to maintain our integrity and fulfill our educational mission. Fortunately, there are several actions we can take to counter feelings of uncertainty, confusion, and self-doubt. Let’s explore five ways we can counter these feelings and find a sense of balance.

First, we can shift our self-talk. It is easy to engage in self-criticism, telling ourselves that we should have said or done something different than we did. We may even question whether we are capable of addressing what lies ahead. Researchers who have studied the nature of self-talk advise that we are better at coaching others than we are at coaching ourselves. They recommend that we shift our perspective and imagine that we are coaching someone else. In fact, they advise that in our self-talk we call ourselves by our names and use the pronoun “you” rather than “me.” The insights and advice offered can take on a different tone and allow us to be more objective and supportive in how we treat ourselves.

Second, we can resist the burden of others’ “should haves” and “shouldn’t haves.” If we allow ourselves to be guided by the expectations of others, we risk ignoring our own experience, judgement, and expertise. In the end, we will have to live with our actions and decisions. We cannot afford to be nudged into bad decisions in pursuit of pleasing others. We also do not have to accept their shaming.

Third, we can step back and take a break. Sometimes just gaining some distance can allow us to see options and develop ideas that can lead to solutions. A break can also give us an opportunity to renew our energy and find some space and distance to clear our minds. It may be tempting to constantly remain engaged and “power through,” but doing so can sacrifice our best work and threaten our emotional and physical health.

Fourth, we can engage our personal and professional networks. We build support networks for times like these. We need to use them. However, we also need to be thoughtful about who in our network to engage and how to engage them. Sometimes we need to talk with people who understand us and can help us to sift and sort our thinking and decide what to do. At these times we may need to connect with a friend. In other circumstances we need to talk with someone who understands the work we do and the implications of options and alternatives and consequences for choices we must make. These are times when we need to connect with a colleague. At still other times, we just need someone to listen and ask clarifying and meaningful questions so that we can become more aware of our thinking and clearer about what we value and actions we need to take. Here, we need to engage a coach.

Fifth, we can give ourselves permission not to know everything. In the middle of complex situations such as we face, there will always be information and motivations to which we will not have access. Assuming we know more than we do can lead to poor decisions. And constantly searching for more information can lead to “decision paralysis.” Often, realizing that there may be information to which we do not have access and understanding that not everything we are seeing and hearing will make sense can help us to remain patient and flexible as situations unfold.

Admittedly, these are difficult times. They can exact a toll on our emotions and leave us feeling uncertain, confused, and doubting ourselves. Fortunately, we have available a variety of actions that can help us to find our way through. However, we need to make the commitment to engage in them to enjoy their benefits.

Six Keys to Remaining Healthy and Whole During Conflict

Not that long ago we celebrated “turning the corner” on the pandemic. The development of highly effective vaccinations held out the promise that the end was in sight. Vaccination appointments were at a premium. Students who had been learning remotely were slowly returning to in-person learning. We were optimistic that much of the conflict and divisiveness of the past year would subside into calm.

While we are closer to the end of the pandemic, not everything has gone as planned. Continuing conflict over masks for younger students, lack of clear guidance from state and federal agencies, and uncertainty and conspiracy theories surrounding vaccinations for older students remain flashpoints at school board meetings, stimulate heated discussions on social media, and provide fodder for cable television.

Meanwhile, on the heels of the pandemic is growing conflict and controversy about the role of anti-racism and the teaching about historical racial issues in classrooms, athletic participation of transgender students, and other cultural conflicts. Much of the energy and organization around these issues are not even originating in local communities. National and regional organizers are recruiting and energizing people to protest at board meetings, make public records requests, and engage in other efforts, sometimes even when none of these issues are on local school district and school board agendas.

Of course, the mix and intensity of these controversies and conflicts vary from school district to school district and community to community. However, the impact on educators and educational leaders caught in the middle can often be devastating. This has already been an exhausting year. Repeated rounds of intense and spreading conflict can take a significant toll on our emotional and even physical health.

In the near term, our ability to reach resolution and dissipate the conflict may be limited. Nevertheless, there are steps we can take to remain healthy and focused despite what is happening to and around us. We are not powerless and do not have to accept being victims. Here are six actions you can take to keep yourself healthy and whole in the face of the conflict and chaos you may be facing:

- Find and maintain a manageable routine. Large scale conflict can become all-consuming. If you already have a set routine of exercise, a regular sleep schedule, and a habit of healthy eating, make maintaining these activities a priority. Time with family and friends also can provide balance and reassurance, so make this time a priority, too. Meanwhile, resist skipping from problem to problem and issue to issue. Decide what most needs your focus and attention and give these issues your full attention. If you panic and lose focus, expect those who depend on our leadership to do likewise or retreat in fear.

- Focus on controlling what you can. Certainly, there are plenty of elements and aspects of conflict that you cannot control. You need to remain alert, but worrying about what you can’t control is unproductive and can be destructive to your leadership and well-being. Remember that you always have choices about how you will respond to what happens to and around you. Herein lies significant power. The choices you make and the actions you take can have a powerful influence on the thinking and actions of others.

- Make listening a priority. During conflict, listening can be among the most difficult challenges, but it is also one of most important actions we can take. We are often experiencing strong emotions. We may have much we want to say. We may feel that others do not understand and need to be corrected. There will be a time for speaking, but our commitment and ability to listen can be a powerful force. Listening communicates respect. Maintaining a high level of respect during conflict can make resolution easier to achieve. Further, focused listening can often give us access to information and clues that will help us to respond more productively and may even lead to solutions.

- Uncover underlying issues. Often the stated reason for conflict is really a symptom or symbolic of the real issue. Fear may lie beneath accusations. Feelings of powerlessness can be behind emotional outbursts. Past grievances can drive current assumptions about motivation. When we understand what is really driving the conflict and chaos we are experiencing, we often gain access to steps and strategies that can move the situation forward.

- Resist responding in kind when we are the object of suspicion and accusations. When people doubt our integrity and accuse us of misdeeds, we can find it difficult not to defend ourselves and employ similar language and behavior in response. Unfortunately, when we do, we are likely to make the situation worse. Doing so can legitimize what others are saying and leave those who depend on our leadership to doubt us.

- Maintain a long-term perspective. Remaining calm and focusing longer-term can be challenging in the middle of significant conflict. The situation can feel all-consuming and the end may be nowhere in sight. Still, we know that what we are experiencing will eventually pass. We and others involved will move on. Meanwhile, we need to be certain not to make decisions or accept resolutions that “sow the seeds” for the next conflict or compromise the integrity and effectiveness of the organization in the future. Sometimes staying in the conflict a little while longer can mean not having to reengage in the near term or live with diminished effectiveness going forward.

Six Virtual Activities Most Likely to Continue in Post-Pandemic Education

When in-person schools were closed and teaching and learning became a virtual activity for most students and teachers, a scramble ensued to design, create, and adapt essential educational activities to a virtual world. Some of the modifications worked well; others did not. Some shifts required time, experimentation, and adjustments to find workable solutions. Yet, over time many activities became comfortable and common place. In some cases, virtual activities and applications equaled or exceeded the benefits of their in-person counterparts.

As plans are developed for the coming year, we need to ask whether some of the solutions and modifications crafted for teaching and learning during the pandemic should continue into a post-pandemic reality. Of course, face-to-face interactions can be more effective for some activities. Yet, assuming that all or most of the approaches and solutions developed during the pandemic should be abandoned risks squandering what was learned that might continue to serve teaching and learning well. Let’s explore six activities that were commonly conducted virtually during the pandemic that deserve to continue in the future.

Many schools transitioned to virtual parent conferences to reduce the danger of viral spread. However, they discovered that more parents, including parents who otherwise might not have attended, agreed to participate. Busy parents appreciated the flexibility to connect without having to travel. Some parents also reported feeling more comfortable and less stressed in a virtual setting. Teachers were able to be more efficient in scheduling and conducting conferences. If a parent did not show up, teachers were better able to make use of the time for other tasks. Virtual conferences certainly can remain an option for parents. In fact, schools can expect disappointment and even resistance from some parents if conferences revert to being exclusively in-person.

The pressure to move quickly and the need to maintain safety protocols meant that many schools transitioned to virtual professional development activities. Since the needs of staff members often varied, virtual delivery offered a vehicle to customize content and support. Further, the pressures and chaos of the transition demanded flexibility for teachers to engage in professional learning when they were available rather than waiting for formally scheduled and structured sessions. Professional learning opportunities responded to real time needs. The convenience and opportunity to focus learning in response to teacher needs argues for continuing professional development in a virtual context for at least a portion of the learning options available to teachers.

With teachers isolating, many school leaders had no choice but to conduct virtual staff meetings. A virtual format offered flexibility to engage staff members despite not being face-to-face. Many staff found the format to be convenient, especially if they were also attending to the learning of their own children or caring for family members. Further, many school leaders made these meeting efficient by providing information in advance and focusing meeting time on crucial issues, needed input, and shared problem solving. A mix of in-person and virtual staff meetings will likely be the choice of many principals and teachers to tap the best of both formats.

Of course, virtual professional team planning meetings were a staple for many grade-level and subject area teams. The virtual format allowed teams to choose the best times to meet, freeing them from the confines of before and after school or formal preparation times. Team members often decided when to meet in response to team member’s schedules, availability, and preferences. Joint lesson planning, shared resources, and problem solving generated renewed value as everyone was struggling to respond to a new set of challenges. Virtual team meetings and planning will continue to be an attractive option for many teacher teams, in addition to in-person sessions.

One of the brighter spots of the pandemic was the rich variety of resources and experiences teachers arranged for their students, including virtual field trips, guest speakers, and other remote resources. Museums, historical sites, and art galleries and other rich sources and supports for learning became much more available and easier to access virtually. Guest speakers found virtual visits to be less time consuming compared to in-person appearances. Distance and many logistical challenges were removed as barriers. Virtual field trips meant access without the expense, inconvenience, and disruption of students having to travel. Of course, there will remain an important role for in-person experiences, but virtual options can open an even wider range of learning experiences.

At first, many teachers and students struggled with strategies to engage students with each other in a virtual environment. However, growing familiarity with technology and more flexible tools led teachers to engage students effectively in virtual student team activities. Breakout rooms, online collaboration tools, and other resources supported shared student dialogue and collaboration. Meanwhile, technology tools allowed teachers to monitor team discussions and activities in real time without having to interrupt discussions. Coaching and redirection could be offered without disturbing other groups of students. Further, the option of recording team interactions allowed for review, analysis, and reflective learning for students and teachers. While in-person student team activities may remain the dominate venue, the availability and familiarity of technology tools to support collaboration will continue to make virtual team activities a worthy option.

We may want to put the past year behind us. However, we need to preserve and leverage what we have learned from virtual teaching and learning to support our work and provide flexibility and efficiency in our professional lives.

Share Your Tips & Stories

Share your story and the tips you have for getting through this challenging time. It can remind a fellow school leader of something they forgot, or your example can make a difficult task much easier and allow them to get more done in less time. We may publish your comments.

Send Us An Email

Do’s and Don’ts for Reattracting Students Who Left

The chaos and uncertainty that accompanied the start of school last fall led some families to explore alternatives for where their children attend school. In some cases, parents decided to transfer their children to what seemed to be the best match for their assessments of the seriousness of the pandemic and the necessary mitigation steps. Some students enrolled in private or parochial schools that committed to start the year with in-person learning. Others transferred to virtual schools so that students would not have in-person contact with others not in their family safety pod. Of course, some students returned to their original school during the year after having a less than satisfactory experience at their new school.

Certainly, protecting the health and safety of their children was a reasonable concern for families. However, the consequence for many schools and school districts has been a significant reduction in enrollment, even though superintendents and principals followed federal, state, and local health agency guidance in their response to the pandemic. Of course, reductions in enrollment can also have significant financial implications.

Now the pandemic is subsiding, and in-person learning will likely be available to virtually all students in the fall. Many school leaders are faced with the challenge of reattracting students who left and potentially attracting other students and families who may be interested in considering a change in their school enrollment. Still, developing and implementing a plan to accomplish this task requires careful thought and insightful actions. Here are some do’s and don’ts to consider as you prepare to address this challenge:

Do:

- Start by discovering the reasons why families chose to leave. Consider personal reach-outs, surveys, interviews, focus groups and other strategies to collect this information. It may be that the reasons are no longer relevant as the worst of the pandemic passes, but incorrect speculation can lead to making the situation worse. To the extent practical, address the concerns of families in your “new normal” as in-person school returns.

- Leverage your “new normal” to inform people of the new opportunities and benefits of attending your school or schools. If you have integrated lessons from the pandemic experience, redesigned learning experiences, developed new learning environments, and made other changes, let stakeholders know through newsletters, podcasts, blogs, and any other means that reach families.

- Make the transition back as convenient as possible. Where practical, streamline the enrollment process. Consider assigning a staff liaison to assist and support families as they transition. An extra level of attention and support may be all some families need to decide to return.

- Invite students and their families to visit the school and experience the “new normal” you and your staff are creating. Feature learning opportunities, social experiences, co-curricular activities, and other opportunities available in the coming year. Fun, excitement, relationships, and rich and varied learning experiences can be compelling as families make decisions.

- Use “relational marketing” or word-of-mouth to support your recruitment efforts. Families and students often rely heavily on the observations and opinions of friends, neighbors, and co-workers as they make decisions about which school their children will attend. The idea of “building back even better” can be a good way of communicating that the benefits of the past will be present and new opportunities will make the experience even better.

- Criticize the opportunities and benefits available at the school in which families enrolled their children. It may be that your school or schools offer far more benefits and better opportunities in multiple areas. However, appearing to disrespect the schooling choice of parents is likely to lead to defensiveness and may work against your goal of reattracting them.

- Don’t blame or shame parents for the decision they made. You may be suffering significant negative consequences due to their decision. You may even believe that their children have not been well-served by their choice. Still, your choosing to point out their mistake is more likely to work against your goal as parents may feel the need to defend their decision. If there are significant differences in your favor, parents will probably sort them out as they consider what you have to offer.

- Don’t assume families and students are not interested in returning. Of course, some families and students will be pleased with their choice to change schools. They may have discovered friends and made connections they want to maintain and will not be open to returning. However, there will likely also be a number of families and students who, if made aware of the opportunities associated with returning, will choose to reenroll in your school or schools. If you choose to ignore the possibility, they will probably stay where they are.

- Don’t accept an initial “no” as a permanent response. Some families and students may not have given much thought to returning. When initially approached with the idea, they may decline. Yet, after more thought and conversations with friends, neighbors, and others, they may become more open to the possibility. Varied avenues of communication, a strong case, and an open and supportive approach may be what it takes to convince them.

Three Phase Summer Plan for Renewal

The pressures and stresses of the past year took a toll on us. They sapped our energy, challenged our resilience, and often humbled us despite our considerable skills and experience. There was no road map to follow and the conditions under which we led the learning of our students seemed to change constantly. Now, as this incredible year is behind us, it’s time to think about how to take care of ourselves and be ready to re-engage when the time comes.

This summer, maybe more than any other, calls for a plan to help us move beyond where we find ourselves. Some people recommend a summer completely disconnected from work. While such a shift can be a good start, as the summer unfolds, we also need to capture what we have learned and how we have grown, and then begin our preparation for a successful start to a new year in the fall. Consider a three-phase plan to renew your spirit and energy, reflect and learn from your experience, and build your readiness to return to the important work of nurturing learning.

The first phase, refocusing, involves letting go and shifting your attention and energy. Now it is time to let go of what has worn you down, tested your resolve, and left you exhausted. Find time to relax, focus on yourself, and do what renews your spirit. You may find that a few good fiction books can refocus your attention and give you energy. Maybe rediscovering and engaging in a long-standing or new hobby can give you the separation you need. Volunteering in an area of significance to you may also be a good option. Returning to a regular cycle of physical activity could be the answer to your renewal. Or maybe your source of renew is spending time with family and friends. The key is to focus on what you need and give adequate attention to your emotional and physical health.

The second phase, reflection, presents the opportunity to revisit what you learned and celebrate wins from the past year. You may find it best to delay this phase until you are feeling renewed and re-energized. With the refilling of your emotional and physical energy tank will come a readiness to revisit the experience of the past year with greater objectivity and perspective. Even though the year presented unusual, even unprecedented distractions and disruptions, it offered opportunities to learn, grow, and meet significant challenges. Reflecting on what you learned about yourself can be an important source of insight and professional pride. The instructional strategies you adapted to a new environment and developed to meet new challenges despite all that was happening can offer opportunities to enhance the experiences of students going forward. Of course, not everything will translate directly to a post-pandemic context, but your reflection will likely uncover a significant collection of options and opportunities to enhance your professional practice.

The third phase, readiness to re-engage, draws on the energy you have refreshed and the insights and understanding you gained from your reflection. You may have identified aspects of your practice that you need to strengthen. You may see opportunities to go add to your instructional tools and strategies. An online or in-person workshop may offer the resources and support you need to get ready. Also, consider reading articles or listening to podcasts on the important impact educators have on the life trajectories of students and how educators often instill hope for students who may be struggling or experiencing tough times. This may also be a great time to reflect on and revisit the reasons that led you to decide that education is your calling and renew your commitment to be the force in students’ lives that will make a difference regardless of their backgrounds, circumstances, and current challenges.

Summer may seem to stretch long into the future. Yet, we know that the time will pass quickly, and we need to take advantage of the break to refocus and renew ourselves. We need to reflect and capture what we have learned. And as the summer passes, we need to ready ourselves to re-engage and continue to make a difference in the lives of our students.

How We Viewed the Pandemic Matters – A Lot

How we view what is happening to and around us makes a big difference. What we perceive drives how we think, how we respond, and what meaning we assign to it. If we perceive an event or action as a threat, we move to defend ourselves. If we see something happening that we think is an opportunity, we explore how we can exploit and benefit from it. If we believe something has nothing to do with us, we will likely ignore it and move on.

The pandemic offers a profound example of the difference our perceptions make in how we behave, especially from a leadership perspective. How we understood what was happening led us to define what options to explore, plans to develop, and actions to take. Now, looking back at what we hope is an experience that is largely behind us, we can begin to see the difference our perceptions have made in the way we responded, managed, and even leveraged the experience for our organizations.

If we perceived the pandemic as a temporary disruption, we were more likely to put in place temporary structures and strategies to help everyone survive until normalcy returned and old processes and practices could be reinstated. On the other hand, if we saw the pandemic as a break from normalcy that offered opportunities to develop, test, and apply new ideas and approaches, this was a time of excitement, flexibility, and learning. It was a time to grow, accelerate change, and build a new normal.

Seeing the pandemic as a temporary distraction likely meant that our leadership focused on making accommodations for needs, challenges, and expectations only to the extent they were demanded. If we understood the pandemic as a challenge to be met, we focused our communication and actions on imagining, innovating, and creating practices and approaches that would continue to serve the needs of learners well after the pandemic has passed. Our energy was given to getting better, not just getting through.

Similarly, if we viewed the situation as something to survive, requests to set aside traditions and long-standing structures and practices may have been granted as temporary waivers that would expire at the end of the pandemic. Conversely, if we saw the needs for change as reasons to rethink and rework assumptions and traditions that may no longer serve as well as they once did, our response likely focused on how the changes could continue to serve learner and organizational needs into the future.

The consequences of these two perspectives continue to play out as we near the end of the pandemic and we are laying groundwork for what comes next. If we perceived the experience as a temporary disruption to survive, we can expect intense pressure to return to life as it was two years ago. Of course, there will also be expectations to return to much of what existed prior to the pandemic even if we treated the pandemic as an opportunity for reimagination and innovation. Still, we have available an array of new options, approaches, and strategies to improve learner experiences, enhance the work of teachers, and move the organization forward in ways not within reach two years ago.

To be clear, few of us viewed the pandemic exclusively as something to survive or an opportunity to be exploited. Regardless of our perspective on the pandemic experience, there remain opportunities to harvest what was learned and apply the lessons it taught us in ways that move our organizations forward. However, we need to move quickly in either case to identify, protect, and support implementation of these new practices and structures before systems re-calcify and change becomes even more difficult.

“Three-Legged Stool” Supports Successful Leaders in Turbulent Times

Now seems like a good time to step back and assess what we have learned and what has been reinforced about effective leadership. The past year has presented challenges that were never imagined. Some leaders excelled while others floundered. For the most part, the success and failure of leaders did not occur by chance.

For some leaders, personality helped them to survive but personality alone was not a formula for success. Other leaders attempted to rely on their technical skills, yet the situation demanded more than tools and techniques. Some leaders tried to “fake it,” acting as though they knew what to do while hoping that others would “pick up the slack,” only to be unmasked at some of the most crucial times.

Meanwhile, leaders who provided the guidance, support, and direction that led to success within their organizations over the past year typically relied on three key leadership elements. We might think of these elements as the legs of a three-legged stool. These “legs” provided the balance, stability, and confidence necessary to navigate new challenges and experiences without losing focus or touch with those who depended on their leadership. The legs maintained strong relationships and instilled confidence while leaders addressed serious and often controversial issues. Let’s explore this three-legged stool and how leaders can utilize it to generate success regardless of the conditions, challenges, and complexity they face.

The first leg is empathy. Leaders who succeed during turbulent, uncertain, and unpredictable times are committed to listening. These leaders know that the insights, experiences, and perceptions of those around them are crucial to understanding reality and what people perceive to be reality. They reflect on what they hear and often test their understanding to ensure clarity and accuracy. These leaders demonstrate caring through their understanding of and concern for the feelings and experiences shared with them. In the end, these leaders seek to see through the eyes of others.

The second leg is vulnerability. These leaders do not claim or act as though they have all the answers to every question and dilemma. They do not deny their experience and expertise. They also do not hide behind their position, past successes, or reputation. They are open and willing to consider advice without feeling threatened or offended. These leaders seek honest, even critical feedback to guide their growth. They readily admit to mistakes without excuses, and they choose to focus on learning and improvement over denial and defensiveness. These leaders want others to contribute meaningfully. In the end, their vulnerability also leads others to step up and step in when they need help and support.

The third stabilizing leg is strength. This strength is not to be confused with the power that comes from position or expertise. While these aspects can contribute to the strength of influence these leaders demonstrate, their strength grows out of words and actions that are consistently aligned with important values. They tap a sense of purpose to guide priorities and develop strategies. These leaders are willing to make tough decisions, even when they may be unpopular in the moment. They are willing to take smart risks to move the organization forward and make necessary changes. Further, these leaders remain focused and persistent enough to see initiatives through, yet they are flexible enough to let go of what has demonstrated that it will not succeed.

Certainly, leaders need knowledge and skills to be successful. They need strategies and tactics to address problems and advance important initiatives. Yet, none of these factors will lead to success, especially during turbulent times, without the three-legged support of empathy, vulnerability, and strength.